Letter From Nicaragua

Two friends wondered, What if we pulled together a group of people who were willing to go where the needs are great, and commit time and money to a three-year project? Here’s what happened when they pursued the idea.

Sun and rain beat down on the tin roof above us

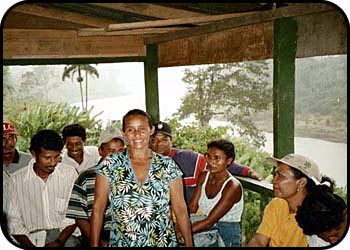

Across from us are 20 residents of Siskiyyari, Nicaragua. (Yesterday we flew in a tiny plane to a dirt landing strip, walked across a small village, and climbed into small boats for another eight hours up the river). We’ve come here to meet with these recipients of “microloans”-chunks of $50 to $200 used by participants to improve their self-sufficiency.

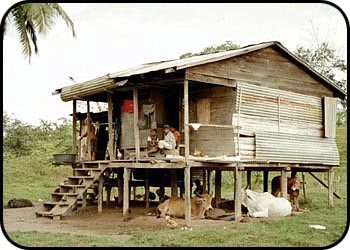

We sit outside on the small veranda of the community “bank,” a one-room wooden structure sitting on stilts with a corrugated steel roof.

The sun, heat, and humidity are punctuated by cloudbursts that announce themselves in waves of sound hitting other steel roofs first. We’re 75 feet above the river, and look out across to Honduras and to undulations of water, jungle and mountain.

The indigenous Miskito people live here and some of them are sitting with us. They are formal, respectful, softly spoken. One by one, they each stand, say their names, and describe how they are using their small loans. A translator named Frances translates from the Miskito language into Spanish. Then, our guide Anuar translates from Spanish into English.

We sense good work, important work being done here, and we so want to help. But it’s hard to know the best way to do it.

In Search of a Good Project

Eight of us have come to Nicaragua in search of a project that we as a group can commit to supporting. My old friend Peter Blomquist and I were talking last summer about the powerful experiences we have had visiting and working in developing countries. Peter is the executive director of Global Partnerships, a Seattle-based organization that supports sustainable solutions to poverty in Latin America. I work as a planning consultant to nonprofits and foundations.

We found ourselves imagining what would happen if some of our friends saw what we had seen. What if we pulled together a group of people who were willing to go where the needs are great, pay their own way, and commit time and money to a three-year project?

We decided to do this experiment, and to do it in Nicaragua, one of the three poorest countries in the Western hemisphere. We assembled a group of eight who come from a range of nonprofit and business experience, though most of us know a couple of the others through some facet of our jobs. We all live in either San Francisco or Seattle, and what we have in common is the desire to push some boundaries, to challenge ourselves with some rough travel and to work together.

Three after-work meetings help us prepare. We all read a lot about the country and try to stifle our inclination to talk—and laugh—about drug regimens, snakes, dengue fever, and being a modified Elder Hostel. Peter has made arrangements through his various connections. All we know is that there will be a focus on micro-lending programs.

So, on February 1, 2001, we arrive in Managua with uncertainty regarding what we will find, what we will learn, and what will emerge for the group as the sort of project we can collectively get behind. We’re definitely philanthropists of some sort. But what sort?

The Education Begins

We meet first with Maria Hurtado, who worked in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for the Sandinista government but resigned after three years due to concerns over the government’s commitment to democratic process. She says to us, “Nicaragua is a punished country.” She is referring to revolutions, poverty, hurricanes, and earthquakes.

The facts are pretty basic. Up until 1979, members of the Somoza family — a father and two sons — ruled Nicaragua for 40 years, and in the process looted, oppressed, and nearly destroyed the country. In 1979 there was a revolution. The Sandinistas — named after the martyred Augusto Cesar Sandino — brought a Marxist, socialist ideology. Included were price controls, land confiscation, press censure, and a command and control economy. Then, with great fears of communism at our back door, the Reagan administration funded the “contras,” leading to ten years of civil war.

Changing geopolitics brought elections and relative peace in 1990, although the last ten years have seen the growth of enormous national deficits and the continued impoverishment of the country as a whole.

We meet with Ernesto Cardinal, one of Nicaragua’s leading artists and poets, and a minister of culture in the early Sandinista regime. This kind, devout man speaks simply and directly of revolution: “A revolution is justified in the face of self-evident tyranny.” He sees the need for dramatic change and hopes that the new generation will rise up.

Later that day we meet with coffee grower Roberto Bendana. “I will tell you about the two happiest moments in my life. First was the Sandinista revolution in 1979. The second was ten years later when they lost the 1990 election.” (He then added, “Well, of course, I should also note the day of my marriage and the birth of my kids!”)

Everywhere we go, we hear of hopes raised and then dashed.

The First Group Meeting

The first group meeting takes place at the end of the second day, when we’re exhausted yet exhilarated by our early interactions. One of us opens the discussion about how we choose our priorities and work as a group.

One member argues for creating a list of all our passions and interests. Another speaks to the need to develop criteria and some rationality for the decision making. A third makes a strong case for letting what is of value just emerge.

The convolutions of all this trigger humorous, yet pointed comments about “process,” a supremely unpopular word among our particular group. There is an instinctive recoiling from the idea of attending group meetings during our Nicaraguan adventure. But we do agree to keep talking every day.

On to Leon

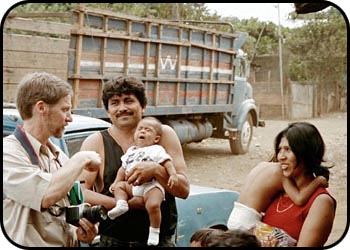

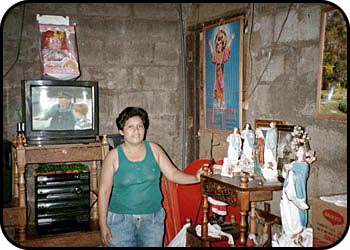

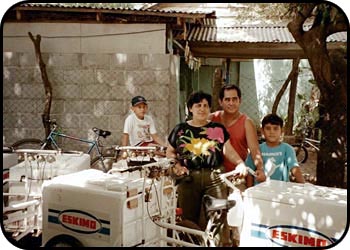

Next, we tour micro-credit projects of Leon 2000, a small community organization located in (and named after) Nicaragua’s “second city.” It has made 2,900 loans of between $50 to $800 to families and small cooperatives though out northwest Nicaragua. We drive through the town of Chinandega, and visit several fabulously charismatic women who have been building small, thriving businesses. One has a tortilla operation that employs four people. Another has amassed 18 three-wheeled bicycles that each hold an insulated container. Riders blanket the town every day selling ice cream bars. A third has an impressive furniture operation. Fat pigs sleep beneath the whiz of the table saws. Each woman has received multiple loans and has paid every one back. Enthusiasm abounds.

We ask to see some rural clients, and we head to the outskirts. The feel darkens, as we drive through rutted, muddy streets with very marginal housing. These are decidedly poorer people. One family receiving a loan uses a primitive machine to fill and seal little plastic bags with a sort of Kool-aid drink. City kids sell this stuff on the street.

Half-way through an upbeat conversation, the mother tells us that the primary benefit of this business is the ability to stay at home with her sick child. She disappears, and returns with a sleeping, extremely frail three-year-old who is fighting meningitis. Then she and her husband are crying, and we’re all overwhelmed.

We head up the Coco River

We fly to Waspan in eastern Nicaragua and climb into boats. The Alistar Foundation, based in Bellevue, Washington, works all along this long river with a variety of projects that help the Miskito people, including funds for teachers, community health, sustainable agriculture and water system development. Fred Gregory is the foundation director and brings 30 years of working in places like Bangladesh, Afghanistan, and Somalia. Anuar Murrar is the country program director. He still carries the results of injuries sustained in the 1970s civil war.

In the boat, Fred and Anuar talk about their concept of participatory development, which relies entirely on community involvement and ownership. They want to show us the early results of the new $40,000 loan pool that is now in place in a small town up the river.

“A Clear-Cut Moonscape”

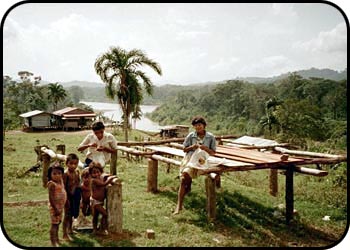

The arrival at Siskiyyari brings back a little of the magical culture shock that used to come so often in my early trips to places that were so different. The town sits squarely in the area destroyed by Hurricane Mitch two years ago. The setting is beautiful and dramatic. The people are really poor, with houses that sit in a clear-cut moonscape of tattered vegetation, a lot of mud, random animals and dirty kids.

The scene evokes different feelings in all of us: some sense dignity and community within these people, others see resignation and poverty.

After the community meeting, we walk around the town. We’re introduced to a man who has been creative in using the resources of the rainforest to create a product that has potential for the marketplace. He is milking the latex from rubber trees to create a rubber-coated fabric that he sews into waterproof bags. He has ideas, vision and spirit, and is eager to learn more. He asks us how people in Guatemala use latex to make things. We talk among ourselves about access to information and knowledge, who has it and who doesn’t, what a difference it makes.

There is no question that there are successes here; the revolving loans are adding income to about 20 percent of the households. The extension of credit is a fascinating development mechanism. Both the Leon 2000 and Alistar programs tell us:

- Approximately 95 percent of people pay back their loans in full

- The programs rely “solidarity groups” of three or four borrowers, or “village banks” of 20 to 25 members, who support each other

- There is no collateral on any of the loans

- There is a large emphasis on training and assistance

Now What?

This has been a very short visit. It would be hubris to act as if we really “understood” these programs and their various opportunities and challenges. Questions remain. For example, we wonder about the point in the development of a “credit culture” in which the nasty side of debt shows its face.

While we’ve talked about all kinds of things, we realize our need to digest our experiences. We agree that we should continue developing the relationships we’ve begun with Leon 2000, and with Alistar in particular, as they are serving a completely disadvantaged group of people in an extremely inhospitable place.

We fly home in a terrifically good mood. Meetings are scheduled to talk about what we have learned and to begin acting. A list of options is coming together.

In all our minds, however, is the knowledge that the real beneficiaries of this trip have been the eight of us. Now we’ve got to give back.

Along with the author and Peter Blomquist, the original group members are:

- Steve Boyd, principal, MacDonald Boyd and Associates, Seattle, WA

- Jim Losi, president, Community Investor Services, Charles Schwab, San Francisco, CA

- Roxanne Hood Lyons, executive drector, Project LOOK, Seattle, WA

- Kris Mayer, program officer, Stuart Foundation, SanFrancisco, CA

- Stuart Rolfe, president, Wright Hotels, Seattle, WA

- Greg Tuke, executive director, Powerful Schools, Seattle, WA