Cross-cultural challenges of working in Nepal

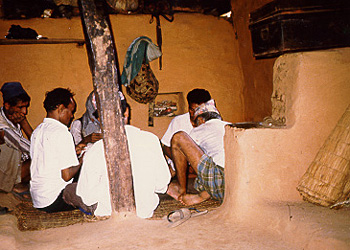

I’m in Nepal, moving on both knees and one hand along the dried-mud floor of Buddha Bahadur Gayak’s house. With the other hand, I’m trying to lay an even line of red cardamom spice path for the Hindu god Laxmi to follow when she comes later in the evening. Each family in the village is constructing its own detailed path of spices, flowers, candles, and food to lead Laxmi to the small shrine in every house.

As the goddess of good fortune, Laxmi’s favor in the coming year is being sought through this day-long set of rituals. Three hours later, we’re done, and we go to the tea stall across the way to talk. Our tea finished, the tea-stall owner walks over, motions Buddha outside, and points to the water tap, where Buddha proceeds to clean and dry his tea cup. The owner, a higher caste member, would not touch such a dirtied item.

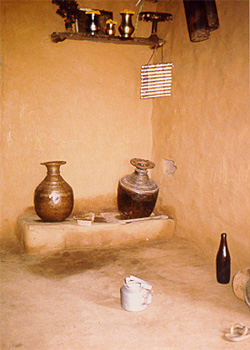

Buddha, 62, is at the bottom of the social system. As a Gaeena, a member of one of four restricted castes, he is only allowed to fish in the lakes and streams for a living. Thirty-five Gaeena families live bunched together outside Pokhara in one of those Third World scenes of rambling shacks, mud, and dust.

I’m interested in Buddha on several levels. One is purely intellectual. As I’ve come to know him, I appreciate the many ways in which we’re different and find pleasure in contemplating these distinctions. On a more practical level, however, I want to help him.

Yet every time I attempt to move beyond simply giving him things – medicine, food – I run into problems. As I sit with him and try to explore a variety of methods to improve his situation, I get no response. He just has no sense of opportunity. He does not regard himself as an individual with “interests,” “rights,” or “needs.” He rarely uses the pronoun “I.” Instead, his comments all seem to refer to his extended family. He doesn’t spend time alone, and he is perplexed at my private process of reading. His beliefs about his life seem cast in stone.

Buddha smiles and laughs a lot, though, is calm, and, despite his hard life, seems at peace. I used to think that he couldn’t be as happy as he seems, but I was wrong. From his sense of himself as a tiny speck in a large cosmos, Buddha derives a feeling of power, meaning, and understanding. You hear it in his voice and in the calm of his rituals. He and other family members described their joy throughout the long, repetitive process of preparing for Laxmi. I had to work at stifling my boredom and discomfort after only 30 minutes of plodding about on the floor.

Our emotions may be the same, but our minds are different. I’ve been taught that I’m “responsible,” an unimaginable and absurd idea for Buddha. I have enormous choice both real and perceived, I can choose what to believe in. I believe my freedoms constitute something valuable and culturally advanced.

Would Buddha be better off if he thought and felt more like me? Should I help him to hold and value such concepts as freedom, opportunity, and the chance to make something better of life?

The scent of change

I explored this question during a visit with Chabi Lal Prasad, a farmer participating in a CARE watershed management project. Buddha and Chabi Lal have much in common, particularly their material poverty and, at the same time, the internal security flowing from their deep sense of connection to their land and people. For Chabi Lal, however, change is in the air. Through CARE, he is participating in an experiment that has important ramifications for his family’s economic and spiritual future.

Chabi Lal’s house sits on a high Himalayan perch in the watershed area of the Begnas and Rupa Lakes. To get there, I walk six hours, climbing 3,000 feet through a lush green valley of magnificent proportions. From top to bottom the mountainsides are terraced-hundreds of shimmering yellow green steps, each filled with the nearly ready rice crop. I climb over a ridge at 6,000 feet and look at a 40-mile length of ice and rock, whose entire length reaches over 23,000 feet-the Annapuma Massif with its six major peaks, only 15 miles away.

“Nepal is so beautiful,” I exclaim as part of my greeting when I arrive at Chabi Lal’s house. I use that typical Western tone of optimism, friendliness, and a tinge of guilt.

“Nepali people are very poor,” Chabi Lal responds, just as typically, with his own characteristic shake of the head. To Chabi Lal, beauty is problematic. He understands my statement, but the rough geography and location of his house contribute to his life’s hardship.

CARE has shown Chabi Lal and other Begnas farmers how to grow and sell bananas, a simple and conventional type of skills transfer. The farmers are making money from it. In fact, the growing of bananas and other fruit is the hottest topic with Chabi Lal and other farmers, largely because it seems to be the fast track to new income. This year Chabi Lal has sold 2,500 bananas at a rupee each. (Average wages per family each month in the hills of Nepal range from 200 to 1,000 rupees.) This is his first experience with so much cash income.

I ask Chabi Lal a question. “Imagine it’s a year later. What has happened? What changes have taken place”? He responds, “I want to sell another 1,000 rupees of bananas. I want the fodder trees to have grown enough so that the water buffaloes eat more and can give an extra liter of milk a day that I can sell.”

When I ask him about what he will use his new money for, he is perplexed. “It’s so obvious,” he says. His answers-new clothes, possible school for another child-show he can imagine new uses for his new income. The development project has given him ideas about progress, risk, and an ability to change his environment.

Risky business

What does it mean “to develop”? What does it mean “to help”? On a recent visit to Nepal, the more I listened, the more complicated and obtuse the answers became. I wanted to explore the hidden risks and costs that come with extending Western-style concepts of “opportunity” to Third World people. I’m not the only one who wants to help Buddha and Chabi.

Such intentions are held by many others and have become institutionalized in the form of hundreds of foreign organizations now helping Nepal. In fact, half of the country’s federal budget comes from foreign aid-about $700 million last year. But the longer I visited, the more I wondered about what all this official philanthropy was accomplishing.

These days, “good” development is increasingly described as a process of transfer. We give something, and we want to ensure that those who receive it can use it when we’re no longer there. Whether it’s the knowledge to grow and sell a banana or the ability to build and operate a hydroelectric plant, the most-valued outcome is self-sufficiency.

Believing the West knows how

Behind this goal is a deeper belief: the notion that what the Western world knows about how to live is good and useful, and that others who don’t live as we do could benefit from what we’ve learned. Development people talk about the need to build a “social infrastructure”, which usually means importing Western-style attitudes, behaviors, and capacities-ideas and attitudes about progress, opportunity, and personal responsibility.

Is there a particular social infrastructure best for all human beings? Are certain attitudes and capacities inherently useful and good? In Nepal, this debate rages. There are knowledgeable, thoughtful people who believe that what might be best for Nepal’s long-term health is a full moratorium on all development dollars.

It’s important to distinguish aid from development. I knew Buddha because I had met his son in a bazaar and heard about Buddha’s need for a new roof, which had collapsed two years earlier. (Buddha and family had moved in with other relatives.) I later gave Buddha $120 to purchase materials to build a new roof. It was a form of simple aid, and it gave me a powerful sense of doing good. But when the next roof falls in, Buddha will have no new skills (except maybe finding a Westerner to pay).

The problem with people like Buddha is that his mind and way of thinking are just not conducive to most forms of development. Buddha would be characterized by many Westerners as “fatalistic.” He has a deep personal sense of not having the option to act upon his world, to mold and change it so that it meets his desires. As you spend time with him, you see that he has evolved a variety of rituals and religious practices that nurture a deep acceptance of what he believes are unchanging, unbendable external realities. These practices infuse every conversation and daily activity.

The impact of change

When the Buddhas of Nepal and other countries in the Third World are exposed to development projects, they will think new thoughts. They will retain their religious beliefs, but their minds, exposed to glimmers of hope, will become mines of intentions, of forward motion.

To follow this process of mental change, we might look at one development project: the Begnas Tal/Rupa Tal Watershed Management Project managed by CARE. It is concentrated in an area of 110 square miles with 31,000 people. The area’s population is increasing at 3% each year. Traditional agriculture and forestry practices have led to a downward spiral of soil degradation, deforestation, erosion, and falling agricultural productivity. Monsoon rains are producing ever-larger landslides, which in turn are forcing people to move farther every year to find animal fodder and fuel for cooking.

The watershed management project’s strategy is to stabilize the physical environment through four distinct, yet interrelated activities: community forestry to protect existing forest and plant new forest; fanning systems to introduce and extend improved agriculture and agroforestry techniques; bioengineering projects to achieve gully control, protect riverbanks, control landslides, stock ponds, improve irrigation canals, and increase the drinking-water supply; and conservation training to develop community understanding of the link between conservation and productivity.

The important concept is one of skills transfer. CARE believes that it can, over time, inculcate the skills involved in the project. But what is really being transferred?

Scientific management

Development organizations focus on fields such as agricultural science-areas of activity that have a clear sequence and are scientifically predictable. There is good reason for this preference: the techniques easiest to transfer are those that can be tested and controlled. “Do ‘A’ and then ‘B’ happens.” A certain amount of water and fertilizer at certain times, in a certain variety of tested soil, and presto: bananas.

Those project elements that revolve around the intricacies of human motivation and behavior are much less predictable, however. For example, CARE wants Chabi Lal and his neighbors to learn collectively how to manage a community nursery that will provide a variety of seedlings to individual farmers. The project also wants to help the farmers develop user groups for government-owned forests, which will be leased to these farmers if they can develop a management plan. Both these goals require a new skill: working collectively in a group process.

There is far less agreement and knowledge about the core ability, or skill, or sensibility necessary to build cohesiveness among a group of Nepali farmers than there is about growing bananas.

Even the simplest element becomes complicated. I asked about a basic group dynamic – when meetings start. If the noted time for a meeting to begin is 3pm, when does it start? I was told that at the most recent meeting a key leader didn’t arrive until just before 4pm. The leader claimed he had no problem getting to the meeting, but he casually stated that “It’s 3 [o’clock] until it’s 4.” Others in the room found this an appropriate response. Do development officials bring forward the Western idea that meetings should start on time and why starting a meeting on time is in their interest? Is starting a meeting on time important in a Third World village?

What if the local caste system is based on hierarchy in which power and authority must play a part-power that is distasteful to our more democratic sensibilities? What if women are excluded from the power structure? There are questions of cultural appropriateness in every step of the development process.

Chabi Lal didn’t start his relationship with CARE believing that he could succeed at growing bananas. The idea of being successful at a new endeavor is the first “input” that has to be transferred. Chabi Lal had to be convinced simply to try, given his experience with past failures of government programs and an original ignorance of the very idea of “improving” one’s condition. Development groups often have to start the process of interaction with farmers by taking them to visit some other location to see others’ success with their own eyes.

The idea of success

When a CARE staff person convinced Chabi Lal that he could be successful at growing bananas, this persuasion was just as much of an input as the banana seedlings Chabi was subsequently given. But such sensibilities are much more difficult to implant, and the techniques for doing it are very ambiguous.

Inputs such as growing a banana, successfully managing a meeting, and convincing a man to believe in a future that is better are pieces of a powerful system of thought that is transferred along with financial aid. Obviously, the economic resources foreign organizations bring are critical. USAID, CARE, World Bank, and others pay the salaries of the Nepali professionals who train farmers in agroforestry and agricultural techniques and ideas. They pay the salaries of “motivators” who work full time in training and motivating farmers for the new techniques and ideas. They pay for every variety of tool and building material.

Development groups expect a transfer of inputs and abilities such that they will gradually reduce their involvement. The process of transfer is incremental and occurs on many levels over the life of a project. One example in the CARE project is the transition to charging the farmer’s money for seedlings. Another is encouraging the farmers gradually to take a more active role in deciding what they want to plant in their community gardens. Another occurs at later stages, as the salaries of the community-garden watchman and motivators can be paid by the user group out of profits generated by the sale of fruit, not by CARE.

The Begnas project was designed with the expectation that, at some point in the next 10 years, it will be finished.

Protecting social values

A good portion of development work takes place at a simple, direct level level that doesn’t sacrifice social values for material ones. For example, when Chabi Lal learns how to grow fodder plants on land previously too steep for agriculture, the material comfort of his life increases. When a donor brings the materials for a new water system and organizes a group of villagers to provide the labor for its construction, the community is left with greater material comfort and the experience of working together. When Chabi Lal learns how to diversify his agricultural techniques to grow bananas for his own consumption, his family’s nutrition is improved.

A more complex issue arises if a development organization influences Chabi Lal to be an active participant in the larger cash economy: a system under neither the development group’s nor Chabi Lal’s control. Chabi Lal now sells his bananas in the market, and he begins to acquire income. Two risks emerge. First is the direct risk of whether it will remain feasible for Chabi Lal to grow and sell his bananas, as the foreign agency reduces its substantial support and involvement. The second risk relates to the larger economic system around the selling of bananas, beginning with the many factors that affect the long-term viability in the local banana market.

These risks are well recognized, and discussed, but hope and sense of opportunity must be fed; Chabi Lal will seek opportunity to the extent that he sees real evidence of his ability to exert control.

Herein lies development’s greatest challenge. If Cbabi Lal’s hope is unfulfilled due to eventual changes in the banana market, what is he left with? Development groups must not abandon programs prematurely in the interest of “self sufficiency.” Once having entered the system, development groups must stay until they can be reasonably sure that the resources they have brought are transferred permanently.

While the idea of self-sufficiency is now a part of conventional rhetoric on social change, the term does bring with it some serious ideological baggage. Do I change Chabi Lai if I act toward him as if he has assets, capacities, resources, and responsibilities?

I think I do but I’ve got to be careful. When a development organization uses “self-sufficiency” and “responsibility” to justify limits in involvement and expenditure, the details of the actual lives of individual men, women, and children can fade into the background.

If we are going to touch people’s lives through development, we must make a commitment to follow through. If we intervene, we can’t default and leave in the name of our cultural value of self-sufficiency. Development organizations must be prepared for forms of sustained commitment over many, many years.

A foot in the West

In Nepal, one can see the clear distinction between economic and social progress. The more I interacted with Nepali people, the more examples I had of individuals who were socially advanced yet economically backward. I noted a calm and joy as people participated in such aspects of life as observing religious holidays and cooking food. Anger was almost unheard of, and I don’t believe it was repressed. I saw degrees of patience that were entirely new to me. In their work, people allowed for margins of time that allowed them to proceed in what appeared to be methodical, careful ways. Relatively little time was spent thinking about money or material advancement.

Buddha also isolates and magnifies a certain irony about the nature of social progress, without analytical thinking, he’s able to practice a variety of basic virtues. He cares about the people around him. I remember my surprise at his sophisticated ability to ask questions about my education, my family, and my beliefs.

This trait – a person’s ability to identify and empathize with the details of others’ lives, especially those who are different in terms of history and ethnicity – has become generalized in my mind as an indicator of a person’s level of social advancement. Such an orientation immediately mitigates another, unfortunate human tendency – the inclination to typecast and stereotype others. Buddha’s economic advancement, when and if it comes, must not be at the expense of his ability to be attentive and aware.

Good feelings

The Nepali people I met were subject to the same core, human emotions as Westerners. I met many desperate individuals whose lives were oppressive and unhappy. But in general, I liked how I was with the Nepalis. I liked what I thought about and felt during and after our interactions. Influence in cultural interactions goes both ways, and I believe my own good feelings are powerful pieces of data about the minds of those with whom I interacted.

Nepal, as with nearly all of the Third World, has a foot in the West. New images and experiences are becoming a part of their cultural lives. Nepalis are increasingly applying new standards to judge what their lives should be like. Sadly, it’s doubtful many of them will be able to meet these new, externally imposed standards. They are not going to have the jobs, the houses, the gadgets and travel experiences that are held in front of them as standards.

I tried to study the effect the West has on the Nepali people, with our focus on economic growth and belief in the power of the individual. The Nepalis I met who were the most Westernized – front-desk clerks, tour guides, language teachers, aid workers – told me they were anxious, sometimes unhappy, and unsure of their future. Their institutions, such arranged marriage, following one’s father’s occupation, were now all being called into question.

Western impacts

A radical new set of abstractions is washing down upon them, including ideas about individualism, internal authority, freedom, human rights, and economic advancement. In listening to Nepali people, I felt the impact of the mass media, with its unidirectional barrage of images flowing from developed country to undeveloped, from West to East.

In fact, my very being-my shoes, my sunglasses, my camera, my shirt, my medicine, my pack-must have been contributing to a sense of deficit on the part of those with whom I was interacting. It was disturbing to confront just how easily needs and desires can be created. Even a glimpse of my flashlight, and I’d created another desire, another wistful response. Needs are created, and I was creating them with every additional day in Nepal.

Interestingly, the major factor that seemed to even out the social relationship between myself and Nepali people was my struggle to speak the language. Sadly, it was about the only skill they had that they thought I desired.

Commitment and balance

The Nepali culture is undeveloped in relation to those elements of culture that Western theorists believe are critical to traditional economic progress and national success. Education, the acquisition of skills, delayed gratification, the work ethic – there is no question that many Nepali people do not have these attitudes and values to the extent that Koreans, Thai, and Singaporeans do.

But these traits, seemingly so valuable, need to be dissected and put in context. A work ethic toward what ends? Delaying gratification for what purpose? Skills built for what activity?

Nepali people have taught me that our Western definitions of progress – with our emphasis on the material and the economic – might need some serious tinkering. Meaning and value can come from many directions. Those who work in development must try to strike a balance, helping Chabi Lal to recognize there are parts of his life that he can affect, yet allowing him to retain his deep sense of causes and conditions – the “contingencies” that allow him to order his life and practice his religion.

Finally, I know now that these really are the “good old times” for deep intercultural experiences. In the coming years, Chabi Lal and Buddha’s children are going to become a lot more like mine. My kids are going to become a lot more like theirs. We have no choice in this. As everything gets mixed together in this global village brew, I hope we’ll be able to use the best of what we can both offer.